The Best Friends Can Do Nothing for You

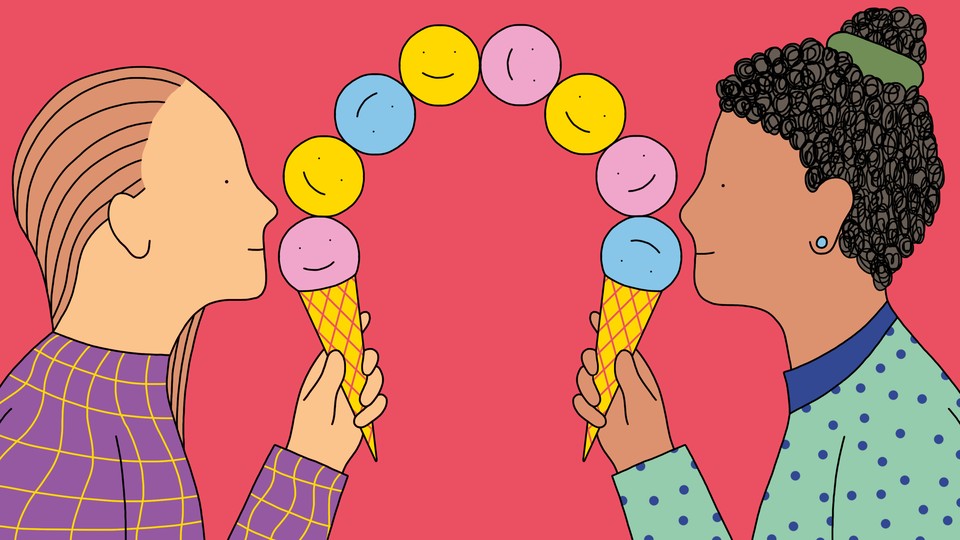

If your social life is leaving you unfulfilled, you might have too many deal friends, and not enough real friends.

“How to Build a Life” is a weekly column by Arthur Brooks, tackling questions of meaning and happiness.

Think for a minute about your friendships. Some friends you would text with any silly thought; others you only call a couple of times a year. Some are people you look up to; others you like, but do not especially admire. You fit into these categories for others as well—maybe you are helpful to one person, and a confidant to another. We get different things out of different relationships, which is all well and good.

There is one type of friend almost everyone has: the buddy who can help you get ahead in life, the friend from whom you need or want something. You don’t necessarily use this person—the benefit might be mutual—but the friendship’s core benefit is more than camaraderie.

These are what some social scientists call “expedient friendships”—with people we might call “deal friends”—and they are probably the most common type most of us have. The average adult has roughly 16 people they would classify as friends, according to one 2019 poll of 2,000 Americans. Of these, about three are “friends for life,” and five are people they really like. The other eight are not people they would hang out with one-on-one. We can logically infer that these friendships are not an end in themselves but are instrumental to some other goal, such as furthering one’s career or easing a social dynamic.

Expedient friendships might be a pleasant—and certainly useful—part of life, but they don’t usually bring lasting joy and comfort. If you find that your social life is leaving you feeling a little empty and unfulfilled, it might just be that you have too many deal friends, and not enough real friends.

Want to stay current with Arthur's writing? Sign up to get an email every time a new column comes out.

Decades of research have shown that it is almost impossible to be happy without friends. Friendship accounts for almost 60 percent of the difference in happiness between individuals, no matter how introverted or extroverted they are. Many studies have shown that one of the great markers for well-being at midlife and beyond is whether you can rattle off the names of a few close friends. You don’t need to have dozens of friends to be happy, and, in fact, people tend to get more selective about their friends as they age. But the number needs to be more than zero, and more than just your spouse or partner.

All the more reason, then, to take honest stock of your friendships. Aristotle offers some advice on doing so in his Nicomachean Ethics. According to the philosopher, friendships exist along a kind of ladder. At the bottom rung—where emotional bonds are weakest and the happiness benefits are lowest—are friendships based on utility to each other in work or social life. These are colleagues, partners to a transaction, or simply those who can do each other favors. Higher up are friendships based on pleasure—something you like and admire about the other person, such as their intelligence or sense of humor. At the highest level are friendships of virtue, or what Aristotle called “perfect friendship.” These friendships are pursued for their own sake, and not instrumental to anything else. Aristotle would say they are “complete”—pursued for their own sake and fully realized in the present.

These levels are not mutually exclusive; you can carpool to work with a friend who has the unfailing honesty you strive to emulate. But the point is to classify friendships by their principal function.

You might not be able to put it into words, but you probably know how these “perfect” friendships feel. They often feature a shared love for something outside either of you, whether that thing be transcendental (like religion) or just fun (like baseball), but they don’t depend on work, or money, or ambition. These are the intimate friendships that bring us deep satisfaction.

In contrast to these real friendships, deal friendships—those at the lowest level on Aristotle’s ladder—are less satisfying. They feel incomplete because they don’t involve the whole self. If the relationship is necessary to the performance of a job, it might require us to maintain a professional demeanor. We can’t afford to risk these connections through confrontation, difficult conversations, or intimacy.

Unfortunately, societal incentives push many of us toward deal friends and away from real friends. The average American worker spends 40 hours on the job during the workweek. In leadership, the numbers are much higher. Most of us work with other people, so during the workweek we have less time for our family than for our colleagues, let alone for friends outside of work. In this way, deal friends can easily crowd out real friends, leaving us without the joys of the latter.

Perhaps deal friendships have displaced real friendships in your own life, leaving you feeling a bit bereft. If this is the case, the hardest part—recognizing the problem—is now behind you. The steps to regaining a healthier friendship balance are fairly straightforward.

-

Give yourself a friendship checkup.

Ask yourself how many people know you really well—who would notice when you are slightly off and say, “Are you feeling okay today?” If you answer “no one,” know that you aren’t alone. In 2018, an Ipsos poll conducted for the health provider Cigna found that 54 percent of Americans surveyed said they “always” or “sometimes” felt like no one knew them well.

For another test of real friendships, try listing a few people, not including your spouse, with whom you are comfortable discussing personal details. If you struggle to name even two or three, that’s a dead giveaway. But even if you can, be honest: When was the last time you actually had that kind of conversation? If it has been more than a month, you might be kidding yourself about how close you really are.

2. Go deep or go home.

Cultivating real friendships can be tricky for people who haven’t tried for many years—maybe since childhood. Research shows that it is often harder for men than for women. Women generally have larger, denser, and more supportive friend networks than men. Furthermore, women generally base their friendships on social and emotional support, whereas men are more likely to base friendships on shared activities, including work.

Recognizing this gender pattern, and also that both of us could benefit from deeper friendships, my wife and I started organizing our social life specifically around conversations about more profound issues. At the risk of becoming Mr. and Mrs. Intense, we directed dinnertime chats with friends away from trivialities like vacation plans and house purchases, and toward issues of happiness, love, and spirituality. This deepened some of our friendships, and in other cases showed us that a more fulfilling relationship wasn’t going to be possible—and, thus, where to put less energy.

3. Make more friends you don’t need.

The key to building perfect friendships is to see relationships not as stepping stones to something else, but as boons to pursue for their own sake. One way to do this is to make friends not just outside your workplace, but outside all of your professional and educational networks. Strike up a friendship with someone who truly can do nothing for you besides caring about you and giving you good company.

Maybe this sounds difficult or awkward, but I assure you it isn’t. It simply requires showing up in places that are unrelated to your worldly ambitions. Whether it is a house of worship, a bowling league, or a charitable cause unrelated to your work, these are the places where you meet people who might be capable of sharing your loves, but without advancing your career. When you meet someone you like, don’t overthink it: Invite them over.

In our go-go world, where professional success is valorized above all else and workism has become like a religion to many, it can be easy to surround ourselves with deal friends. In so doing, we can lose sight of the most basic of human needs: to know others deeply and to be deeply known by them. Christians and followers of other faiths place this deep knowing at the heart of their relationship with God, and it is central to achieving change in psychotherapy.

One of the great paradoxes of love is that our most transcendental need is for people who, in a worldly sense, we do not need at all. If you are lucky, and work toward deepening your relationships, you’ll soon find that you have a real friend or two to whom you can pay the highest compliment: “I don’t need you—I simply love you.”