What do bicycles and social media have in common? Soon after being adopted, each of these technologies brought on a tsunami of unjustified moral panic. Let’s start with bikes.

When bicycles burst onto the Victorian scene in the 1800s, they were a big deal. This cool contraption made it possible to travel much further and faster than you could ever go on foot. Better yet, bikes were a lot cheaper than horses (not to mention simpler to maintain).

Soon enough, bicycles gained popularity with a group whose transportation options had historically been limited: women. At that time, if women wanted to get somewhere without walking, they’d typically need someone to take them there, in a horse and carriage. Usually, that would be the patriarch of the household. And if he was unavailable or unwilling? Tough luck. Hoof it or stay home.

With bicycles, women could be more independent than ever. Awesome, right?

Not according to those in power. Instead of celebrating the new-found freedom the bicycle had brought, authorities drummed up a spectacular display of moral panic.

Here are the dangers of the bicycle, according to many of the era’s medical “experts”:

- Bicycles would transform women’s feminine gait into a ghastly, ugly walk, characterized by “a plunging kind of motion.”

- Women would suffer from “bicycle face,” a permanent consequence of being exposed to the air at superhuman speeds.

- Women’s delicate bodies would break down from the strain of riding bicycles, leading to appendicitis, infertility, and even psychosis!

In hindsight, these ideas are ridiculous. But back then, they were widespread fears, and they were amplified by manipulative people who wanted women to be docile and dependent.

Is social media the new bicycle?

Fast forward around 125 years. Today, many widespread beliefs about modern technology mirror the Victorian moral panic over bicycles. For example, every parent “knows” social media is awful for teenagers’ mental health…but is it?

In 2017, The Atlantic published an article by Jean Twenge called “Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?” The article went viral because it made terrifying claims, including, “Teens who spend three hours a day or more on electronic devices are 35 percent more likely to have a risk factor for suicide, such as making a suicide plan.”

Although excessive social media use among teens is correlated with higher self-reported mental health issues, the effect is extremely small. In fact, it’s so small that it’s almost insignificant. As I explained in my recent Medium column, a look at the raw data discussed in that article reveals that the effect of social media on teen depression is roughly equivalent to the effect of eating potatoes. Unless potatoes are also “destroying a generation,” social media is probably not worth the panic.

To her credit, Twenge recently published an article that’s far more measured and accurate. In fact, it powerfully refutes the claims she made in the 2017 article. The article is a review of her new survey of 1,523 teens, which dives into how they’ve been doing throughout the quarantine.

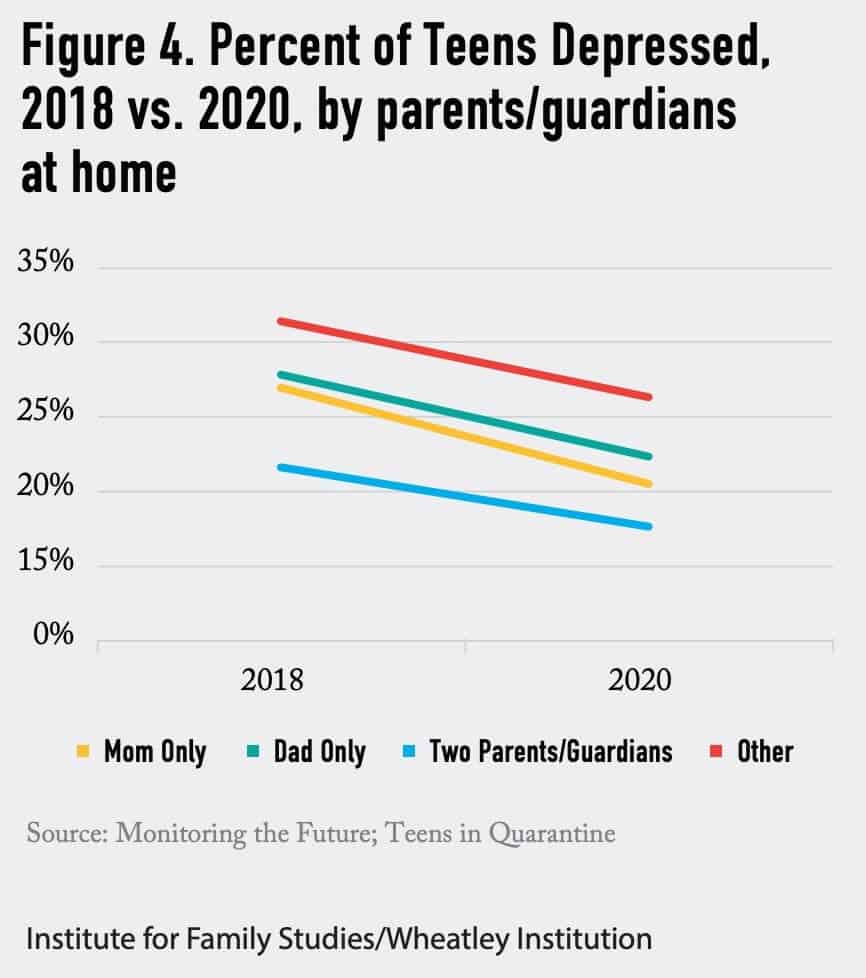

As it turns out, teens have been doing surprisingly well during the quarantine. That’s been especially true during the school year: rates of depression dropped dramatically, as did rates of loneliness.

From Twenge’s new research paper:

“27 percent of teens in 2018 were depressed, compared to 17 percent during 2020 with school in session, and 20 percent in 2020 with school out of session.”

That’s a dramatic improvement. To put that in perspective, adults were three times more likely to experience mental distress, anxiety, or depression during quarantine.

Did teens’ improved depression numbers result from decreased social media use?

Nope.

Teens are spending the same amount of time on social media now as before. To be totally accurate, their average amount of social media time dropped slightly—by about 15 minutes per day. It was replaced by other on-screen activities, like watching TV.

It appears the forgone conclusion in Twenge’s original article showing that teens who spend more time on devices are more likely to have a “risk factor for suicide,” likely got the causality reversed. It appears kids more likley to have risk factors for suicide are also those who seek escape by spending more time on their devices.

Why teens are less depressed during quarantine

The research shows that there are likely two explanations for teens’ reduced rates of depression:

- They’re getting more sleep, and

- They’re spending more time with their parents and siblings.

During COVID-19 lockdowns, huge swaths of teens experienced an increase in sleep and family time. These changes were much more dramatic than the 15-minute reduction in daily social media use, and according to Twenge herself, these two factors were responsible for the improvement in mental health.

From her new article in The Atlantic:

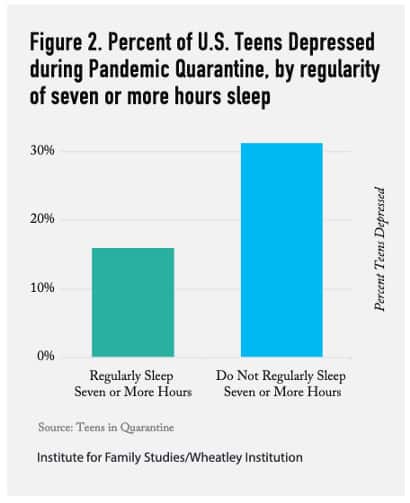

“Teens who are sleep deprived are significantly more likely to suffer from depression. In 2018, only 55 percent of teens said they usually slept seven or more hours a night. During the pandemic, this jumped to 84 percent among those for whom school was still in session.”

Scientists have known for many years that teenagers naturally tend to wake up later than adults. During quarantine, students have been waking up later: just in time for virtual classes to start. Since sleep is a huge factor in depression, it’s no surprise that teens are less depressed under these conditions.

The other major factor is family time, which has also increased during quarantine. According to the article:

“68 percent of teens said their families had become closer during the pandemic. Family closeness was associated with mental health: Only 15 percent who said their families had become closer during the pandemic were depressed, compared with 27 percent of those who did not believe their families had become closer.”

As it turns out, the extended quarantine has served as a groundbreaking natural experiment, and the results are clear. When our kids get more sleep and family time, they’re less depressed.

Instead of panicking about teens’ social media use, what if we focused on sleep and family? In other words, what if we paid attention to the real problems?

But we don’t, because the real problems rarely make viral headlines. In the coming years, the moral panic over social media will likely continue to distract us from those more important, less sensational problems. After all, even though this 2020 research refutes the very same author’s 2017 article, the old article will probably continue to get more eyeballs.

Are we doomed to repeat history?

The Victorian moral panic over bicycles was a mistake. Today, we can all see that. But at that time, the panic had consequences. It prevented many people, especially women, from being able to exercise the freedom they deserved. Many people who could have benefited from using bicycles ended up worse off because of an irrational panic over the new technology.

Social media is a new technology that has sparked a similarly irrational moral panic. Succumbing to that panic has consequences. As just one example, data suggests that social media may help reduce suicidality among LGBTQ+ youth, because it’s empowered them to connect with supportive people and discover that they’re not alone. If we succumb to moral panic about social media, we might harm that group. Like the bicycle, social media has many benefits, and it’s unethical to make sweeping claims about its harmfulness without nuance.

“No one got upset when bicycles showed up,” Harris proclaims.

Now, you know better than Harris did at that moment. You know that lots of people got upset when bicycles showed up. You know that the outrage was baseless, and you know that the moral panic had real consequences for real people.

This time around, let’s avoid repeating history.

Related Articles

- Schedule Maker: a Google Sheet to Plan Your Week

- Habit Tracker in Google Sheets – Free Template

- A List of 20 Values [and Why People Can’t Agree On More]

- Timeboxing: Why It Works and How to Get Started in 2024

- An Illustrated Guide to the 4 Types of Liars

- Hyperbolic Discounting: Why You Make Terrible Life Choices

- Happiness Hack: This One Ritual Made Me Much Happier